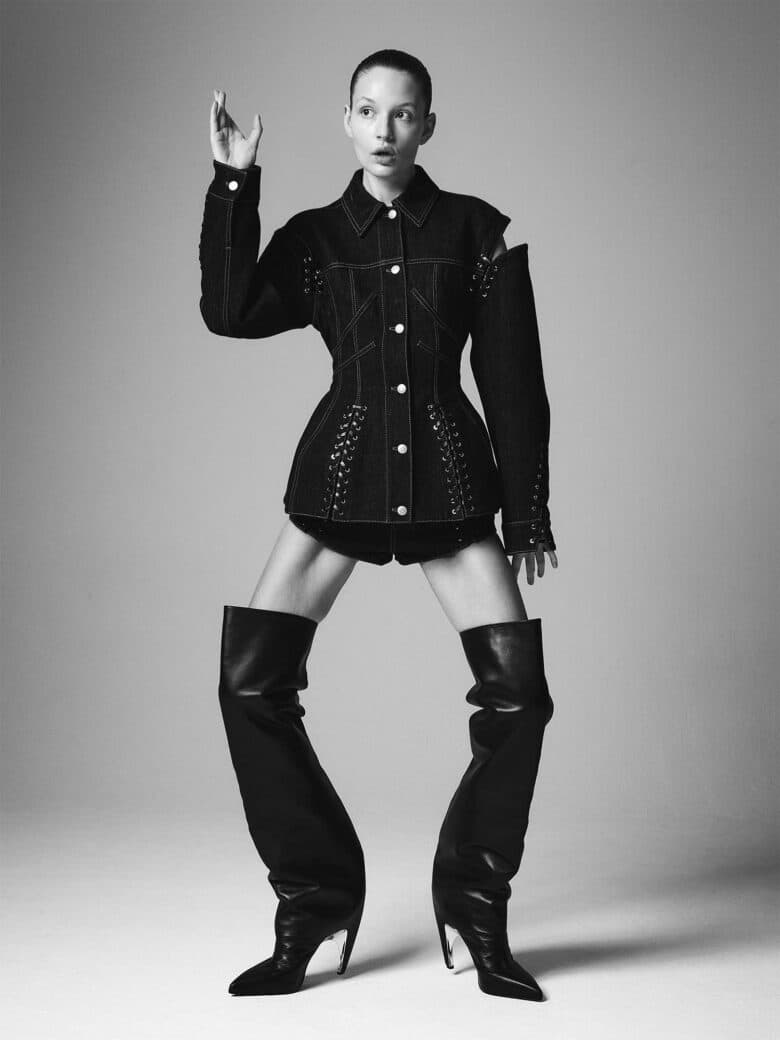

Megan Nolan on addiction, true crime and the runaway success of her second novel ‘Ordinary Human Failings’

Though you might not have realised it, the chances are that you’ve read something by Megan Nolan. Her personal essays have appeared in everywhere from The Guardian to The New Yorker, plunging headfirst into topics as innocuous as tattoos, and as complex as religion. There’s her debut novel Acts of Desperation, a gut-punching exploration of destructive romance that approaches the subject unabashedly. As Nolan puts it (very modestly), Acts of Desperation is a “millennial messy girl novel”. Then there’s her second book, Ordinary Human Failings, which came out in the UK last summer to heaping acclaim. Her sophomore work, a dissection of an Irish family in the wake of unimaginable tragedy, is palpably more ambitious than her first. Ordinary Human Failings earned her a place on the shortlist for the Gordon Burn Prize and the longlist for the Women’s Prize for Fiction. It even made its way onto the Fallon Book Club. As you can probably tell, trying to identify Nolan’s “niche”, it’s difficult. “I haven’t got a great attention span, so I feel like I’m not the kind of person who’s going to have a very consistent body of work,” she tells me over Zoom.

Nolan has always known that she wanted to write a “family novel”. She didn’t, however, possess “any particular instinct on how the family would come to be”. In the end, the reclusive Irish family at the centre of Ordinary Human Failings found their footing by way of something Nolan had heard about Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper. “A tabloid had approached Sutcliffe’s family, who were all quite working class people. They didn’t have a lot of money and some of them were severe alcoholics, and this journalist had approached them and been like ‘Do you want to come and stay in this hotel? We’ll give you some pocket money and some booze. But the condition is that you can only talk to our newspaper’”. For Nolan, a moment of such “insane pressure” was the perfect catalyst for Ordinary Human Failings and everything that unfurls within its pages. And a lot does unfurl.

Unlike Acts of Desperation, Ordinary Human Failings is sprawling in its focus. Not only is each of the Greens meticulously yet tenderly examined, but we jump back and forth between 90s London and 70s Ireland, where the reader learns how the grim realities of her second novel came to be. It’s hard not to use words like “grim” when it comes to a book like Ordinary Human Failings. Even The Guardian felt it was best to describe Nolan’s work as one of “misery”. But what Nolan does so brilliantly is find the moments of vibrancy in what can seem like pervasive darkness. She injects convincing nuance into situations that are seemingly black and white.

Megan joined our call from the New York apartment that she upheaved her life in London for. Before she relocated to the Big Apple, Nolan lived in Dublin, though she was born in Waterford, a small seaport city in the southeast of Ireland. Nolan has talked at length about the media’s demonisation of her hometown. Ballybeg, the estate she grew up on, was featured on a list of “Ireland’s Estates from Hell”, because of its “drug gangs, feuding traveller clans and violent money lenders”, as the writer for The Irish Independent put it themselves. Nolan can’t relate to this sordid depiction: “I suffered no poverty, no exposure to addiction, no violence” she said in an article for The Guardian. But the way Ballybeg has metamorphosed in the cultural imagination was a source of inspiration for her second novel. More than that, it was something she tried to remedy through Ordinary Human Failings. “Now that I have a more grounded sense of identity and I’m myself fully, I would be able to live there again. And I do want to live there again at some point” she tells me.

HUNGER sits down with the author to explore the nuanced portrayal of addiction in Ordinary Human Failings, as well as Nolan’s insights into the complexities of human behaviour.

Amber Rawlings: Congratulations on being shortlisted for the Gordon Burn Prize. How does it feel to get an accolade like that? When I spoke to Eliza Clark, she said these kinds of accolades can sometimes be quite pressurising…

Megan Nolan: I’ve never actually won any awards. I’m kind of used to getting shortlisted and not winning, so it feels very low stakes to me. I mean, it sounds kind of banal to say it but it’s just nice to be in the company of other people. Like, Paul Murray is one of my big writing heroes, and we were nominated for the same prize recently. The fact that I’m even being considered alongside him is really meaningful to me, you know? I lost to him, but I was like ‘good’.

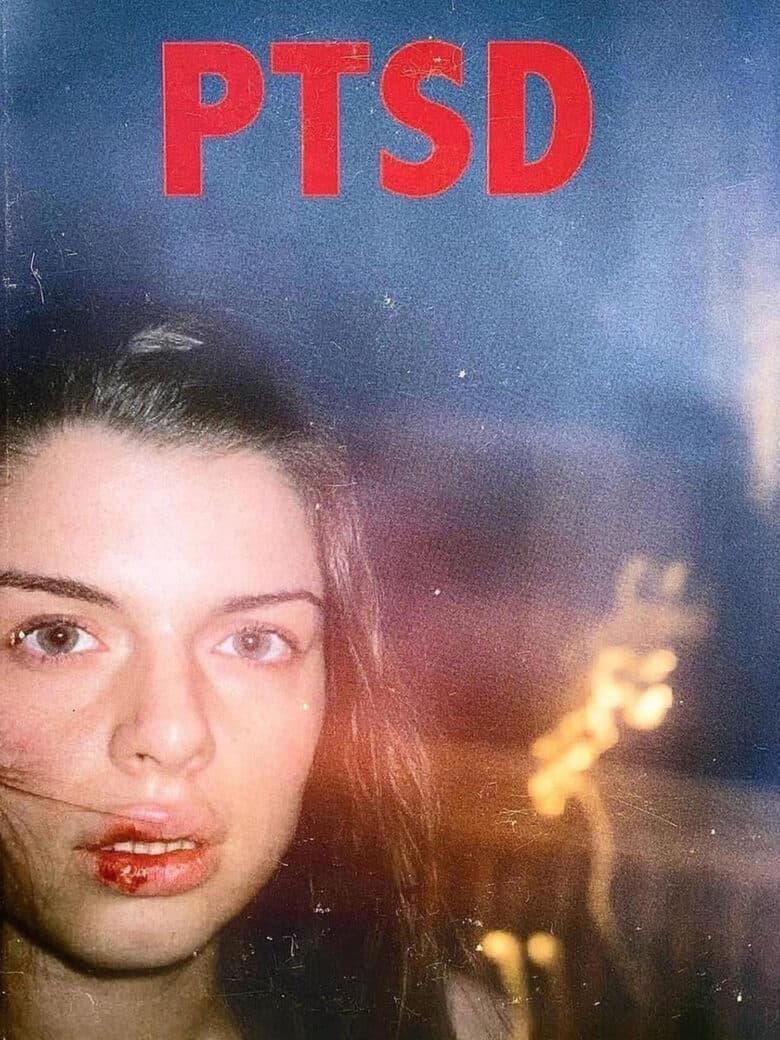

AR: With Ordinary Human Feelings, some people would call it a crime book, and others would call it something else. How do you see it and how did it come about?

MN: It’s been interesting seeing how it’s classified in different places. It just came out in the US and I see it in crime sections sometimes, which does feel really weird. I love genre fiction and I read a bunch of horror and crime stuff but it’s definitely not what I set out to do. It’s not a classic crime story. Basically, it came about because I’d always wanted to write a family novel, but I didn’t have any particular instinct on how the family would come to be. And I had read Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son by Gordon Burn; there’s a part about Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, and how a tabloid had approached Sutcliffe’s family, who were all quite working class people. They didn’t have a lot of money and some of them were severe alcoholics, and this journalist had approached them and been like ‘Do you want to come and stay in this hotel? We’ll give you some pocket money and some booze. But the condition is that you can only talk to our newspaper’. I don’t know if that actually ended up happening, but certainly the offer was made. I thought that was a really great, very simple premise to display a family because it’s like this moment of insane pressure and crisis. I didn’t have any ideas about the family themselves until I started writing during the COVID-19 lockdowns. I was really missing home and I thought ‘okay I’m going to write about a Waterford family’, which is where I’m from.

AR: From that answer it sounds like you weren’t thinking about this, but were you ever worried about Ordinary Human Failings becoming pigeonholed as something it’s not?

MN: I think if I had written something in a genre for my first book, then maybe I’d be a little more concerned about that. But no, actually. My worst nightmare would have been to have written a very similar book to my debut and to be like ‘okay, here’s the second millennial messy girl novel’. That was the only thing I really didn’t want. The things I’m thinking of writing about for my next book are also from quite a different genre, and that just feels kind of fun to me. I haven’t got a great attention span, so I feel like I’m not the kind of person who’s going to have a very consistent body of work.

AR: Ordinary Human Failings is such a different tone to Acts of Desperation, mainly in the sense that you’re investigating so many different characters rather than honing in on the inner life of one person. Which style do you gravitate towards more?

MN: In a way I don’t really have an answer because I’ve only done two books and they’ve both been so different. I don’t think I would have been comfortable doing the third person perspective that’s in Ordinary Human Failings for my debut novel because I was coming from a position of having done journalism and personal essays for years. It felt more natural to be in the first person. There is something fun about creating a really intense reading experience and being completely submerged in this one person. But in terms of servicing a story, it’s not the most effective thing. And I don’t think it would have worked for Ordinary Human Failings, because part of the premise was how the community and the wider world see this family.

AR: I read your essay for The New Statesman about how binary a lot of the discourse around addiction and recovery is. That’s a recurring theme in your work — do you think that always will be?

MN: Yeah, I do. Not necessarily substance abuse, but definitely there’s something about addiction. Obviously addiction is in itself a very compelling subject and it can be very dramatic and very tragic as, like, a social issue. But it’s what’s at the core that’s more interesting to me: the different ways that everybody experiences dissatisfaction and how they try to evade that feeling. In Acts of Desperation a key theme is that she drinks too much or takes too many drugs or whatever. But she’s also using the relationship as a means to do the same thing, which is just to escape her own body. She craves these moments of absconding from the intolerable reality of living in her body. The cause behind addiction will always be a part of what I’m interested in writing about. I’ve read a crazy number of addiction memoirs and I do just find the whole subject endlessly compelling. I’ll always want to read an account of somebody’s addiction. It’s the pathos of self-created pain, you know? When somebody is, technically, the author of their own pain. Obviously that’s complicated, but it’s like, how much willpower do we really have?

One addiction memoir that I really love is Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man by Bill Clegg. I picked up a copy I found in this sublet when I was in New York last year. I was openly weeping in a restaurant reading it. He developed this terrible, crippling alcohol and crack cocaine addiction, and there’s all these scenes of him spending crazy amounts of money to just be in a hotel room on his own. After I read it, I looked him up and sent him an email saying ‘I read your book. It’s amazing’. And now he’s my agent. So, yeah, a full circle moment.

AR: Ordinary Human Feelings is a very sad book, but you inject it with so much life and vitality. Did you ever find yourself succumbing to the sadness, and did you ever find yourself trying to make it too hopeful to remedy that? What was the writing experience like in that sense?

MN: I was definitely aware of that towards the ending. I didn’t want to end on a note of complete despair, I just didn’t feel that that was correct. But given the subject matter, it would also be very inappropriate to be like ‘and then they were all fine and had a good time’. I had to find a balance between those two things. It definitely does end on a hopeful note, but it’s not a happy note. The only thing I really struggled with was writing the part where Richie, the alcoholic brother, is just destroying his life. When he has that job in a restaurant and then he gets really fucked up one night and destroys the restaurant. Part of what makes writing interesting and useful to me – and hopefully to the reader – is exercising different things that you’re afraid of: writing outcomes that you fear in life. With [Richie] I could have written that character and been like ‘I’m gonna let him get clean’. I could have written the outcome I wished for. It was tough, and it hit a little bit close to home. Genuinely, none of the characters are specifically based on anyone that I know, but they’re all sort of related to types of people that I know in Waterford. I had this relative who died a couple of years ago who was a really bad alcoholic and he was for probably my entire life. He would have died when he was maybe less than 60.

AR: Speaking of Waterford, I read your essay for The Guardian about how you at one point felt very negative towards it. Did writing Ordinary Human Failings help remedy your thoughts about where you grew up?

MN: I think the longer you’re away from your home, the more nostalgic you can afford to be about it. I’m sure if I lived there then I’d have significant problems with it again, but I’m very romantic about it now, and I do really love Waterford. I think the reasons I didn’t like it were just the same as anyone who doesn’t like the small town that they’re growing up in; they have bigger ambitions or whatever. In a small town in Ireland, you can’t really do a lot without being called out on it. I think that’s why I’m now gravitating towards big cities. I’ve spent the last ten years in London and now I’m in New York, because if I’m the focus of attention, I become too self conscious to do anything. I really need to be in a place where nobody cares about anything I’m doing, you know? The scrutiny of living in a smaller place was not good for me. But I think now that I have a more grounded sense of identity and I’m myself fully, I would be able to live there again. And I do want to live there again at some point.

AR: What do you think about the state of true crime right now? How do you think it’s changed since the heyday of tabloid journalism, when Ordinary Human Failings is set?

MN: I’ve read true crime since I was a young teenager, but it’s become such a big cultural moment in the last ten years. It’s something that I find hard to have a definitive stance on. Like, Gordon Burn ostensibly could be said to be a true crime writer, but he’s a genius, and to call his work true crime suggests that he’s trash. The journalist Amelia Tait wrote something really good about how the families of, for example, a murdered woman don’t really get any intervention if a big buzzy podcast is made about their relative. And I think that’s inevitably going to be the case with almost all of those things; pretty much every true crime book will have a family member who does not want it to be written, you know? I think that’s an inescapably icky thing. And I don’t really know the way around that because we’re never going to stop finding crime interesting. That’s our very nature.

AR: Tom, the tabloid journalist in Ordinary Human Failings, has all the makings of a character that readers will hate. Amazingly, though, he has redeeming qualities. Was it hard finding those?

MN: No, it was almost the opposite. I started out with him being a good person in my head, then I had to degrade him a bit. He was kind of inspired by someone I saw when I used to do shifts at Metro years ago. There was a new staff training day and I was with people who were starting at the Daily Mail, which was in the same building as Metro. There was this really sweet boy who was, like, 20. Like just out of school or college. He’d just arrived in London and was very naive and very, very kind. And I was just thinking, ‘Oh my God, like what is the Daily Mail going to do to him? What are the things that he could be persuaded to do even though he’s essentially a decent person?’ Some of the stuff they publish in those kinds of newspapers is so comically evil that you think the people working there must be these cartoon villains, but most of them are fairly normal people, you know?

AR: An essay you wrote for The New Statesman talked about how harmful Goodreads is to literary culture. How do you find being an author in this age in that sense? Do you like the way social media can amplify your voice, or is there some level of resistance to how the message of your book could be diluted?

MN: Yeah, it’s funny. I was very online before I was a writer, you know what I mean? I didn’t grow up with the internet and I was probably an adult by the time I was fluently using it, but I’ve always had an active online presence. If I was a different kind of person and I’d released a novel and the publishers were like ‘time to get an internet presence’, I think I would have hated it. I’m fluently engaged with the internet, but I think it’s a bummer that if I wasn’t, but I’d written a really great book, I would be suffering from that. Like, when my book came out in the US… There’s so little money in the publishing industry now in terms of what a publisher is willing to do to market your book. Unless you’re like a proper star they’re not flying you around the country on a tour or organising a big party for you. But because I knew all that, I made sure that I organised parties and there was a full lineup of events. But if I didn’t know how to do those things, it would impact the impression that others have of the book.

AR: You’ve already tackled such big themes in your first two novels. What do you see yourself taking on next?

MN: So I’m just starting to write a new novel now, and the two things that I knew I wanted to write about were a man and woman who are extremely close friends as adults. Who are in romantic relationships with other people, but have an unusually close friendship. That’s something that I’m experiencing myself right now. I’ve always had very close male friends, but now people are getting married and stuff, it’s like ‘Oh, so how does it work?’ And then I have another idea. I went to see this show about Pierre Clémenti in MoMA last September. He was this radical actor in the sixties, I think. But now Pierre’s son is in his eighties and he kind of just goes around presenting his father’s work to museums and galleries. He’s spent his whole life promoting his father’s estate and his work. I thought that was such an interesting idea: the kid being the caretaker of the cultural product. It’s those two ideas that are involved in my new book.

Ordinary Human Failings by Megan Nolan is published in paperback by Vintage on the 4th of April 2024.