Revisit Willy Spiller’s seedy, glamorous images of the 70s New York subway

In 1977, just before the photographer Willy Spiller left Zurich for New York, an artist friend living in the city told the then 30-year- photographing the seedy but old:“Open your eyes. You arrive in NewYork for the first time only once.” In the years that followed, Spiller would take this advice to heart as a freelance photojournalist in the heart of NYC, producing a collection of Seventies and Eighties New of stark, candid and colour-saturated images documenting the city and its people in Queens or at the likes of Studio 54. Speaking over the phone for this interview 46 years since he first stepped foot in America’s cultural hub, his friend’s advice still rings true.

“Everybody wanted to go to New York. That was the place to go because it had a great influence on fashion, music and culture,” says Spiller, who had studied art and design in Zurich and also worked as a local reporter and photographer. “It sounded like the drive and dynamic was great. And so it was.”

The night Spiller landed in NYC in May 1977, he walked up to the Chelsea hotel with very little money in his pocket. The Chelsea was a haunt for actors, musicians and artists like Andy Warhol and Patti Smith, and a commune for struggling and emerging artists. The hotel was cheap, which suited Spiller. When he went out the next morning, he was taken a back by what he saw on the streets.

“I was quite shocked and afraid of everything,” he recalls. “I was just looking! Someone even shouted, ‘What are you staring at?!’ Everything was strange, new and fascinating. For Americans it was normal to have a crossroad with three gas stations and a supermarket. For me it was crazy. In order to visualise that, my European eyes were very welcome and that was the basis of my existence there.”

By then, the music scene in New York was booming across places like the Lower East Side. Studio 54 was mobbed by people who wanted to catch a glimpse of the club’s frequent famous faces. “They also had very boring people from New Jersey in there so that the trendy crowd from New York could feel even better and think how special they were,” Spiller remembers. Finding himself amid the lights, music and famous people, and truly immersed in the unfamiliar sights and sounds of the Big Apple, Spiller then went down into the subway.

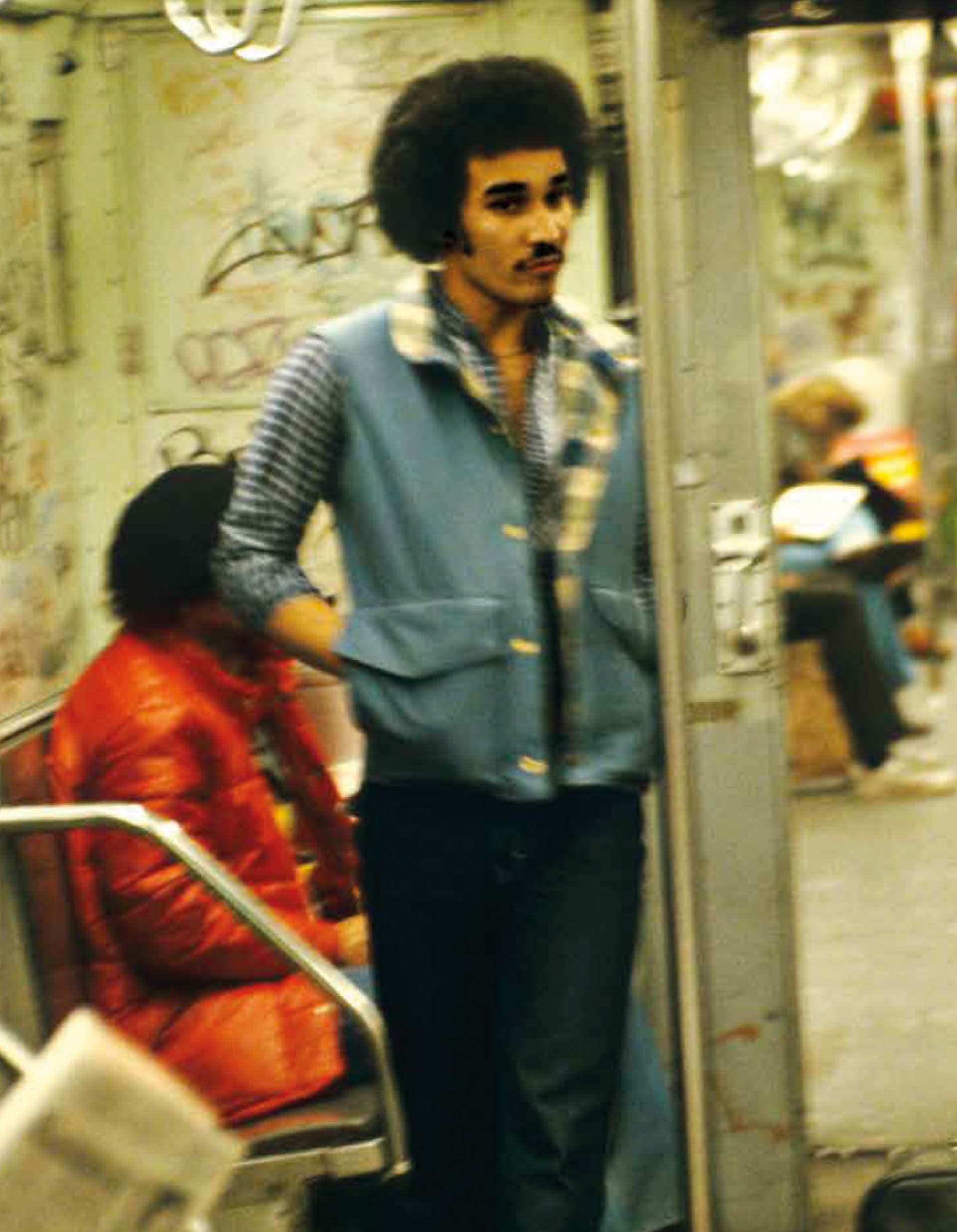

“Forever a lover of fairy tales, I was always enthralled when I plunged into that rattling world of these mobile metal living rooms, like Alice in Wonderland, never knowing whether the next moment would be threatening, violent or funny, frightening or delightful,” he says. “Here I could blithely observe and capture the vast human menagerie of the metropolis. Communication between passengers, if any, was subtle. People randomly crammed together for the length of a ride appeared as though they’d rather ignore all differences – status, culture, ethnicity, religion, gender and age. They seemed equally exposed and uninhibited – as if they’d checked their private lives in above ground – curiously indifferent to me and my camera.”

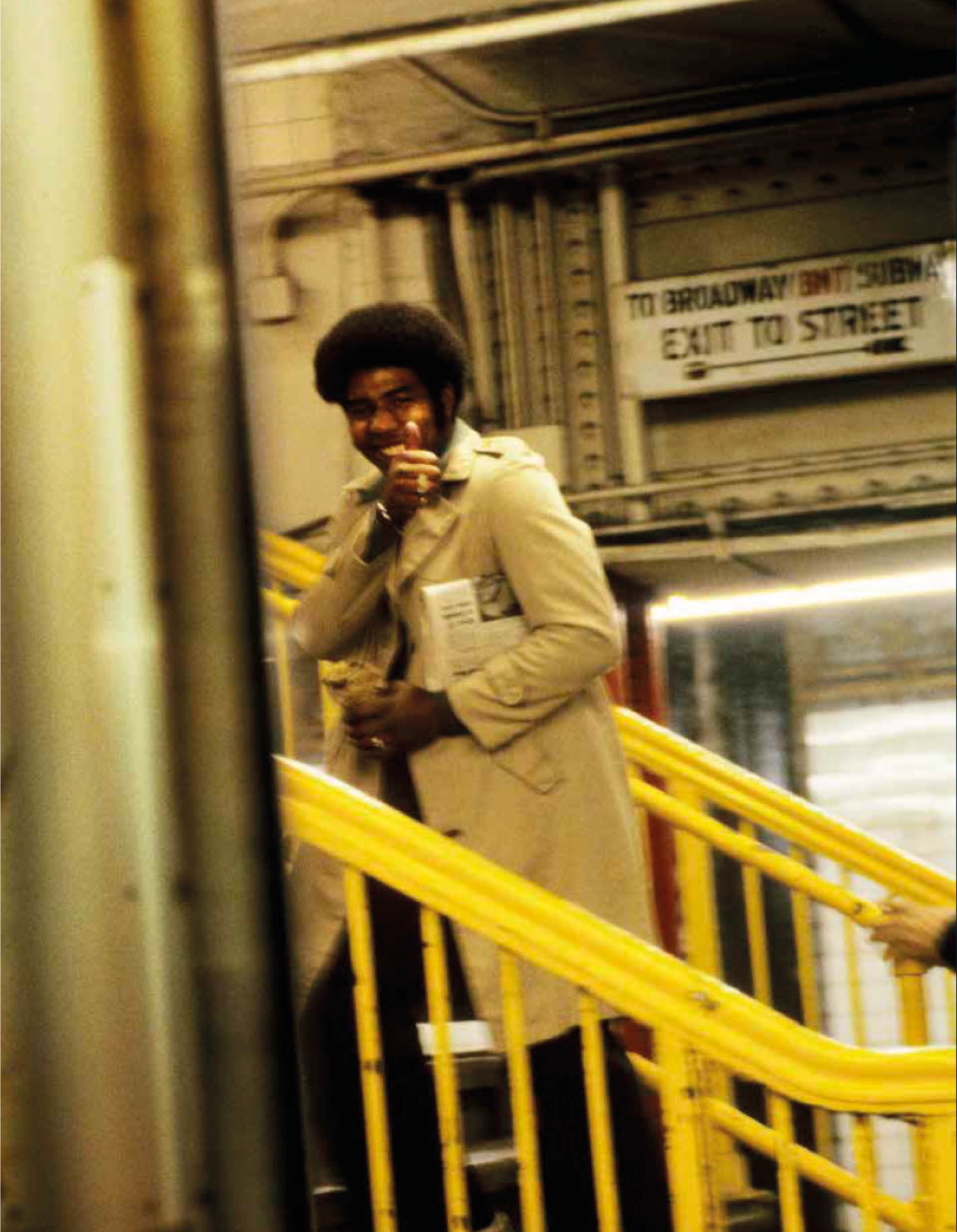

Spiller offered his work to publications like Stern magazine, La Repubblica and Paris Match. Japanese publications like The Asahi Shimbun were fascinated by the subway. “I realised that this could be a long-time project for myself,” he recalls, sharing how nobody liked the subway and that was why it was ubiquitously known as Hell on Wheels, that New Yorkers hated the dirt, noise and heat of the carriages, and they could not understand why a strange man with a camera was taking pictures.

Halfway through our call, Spiller presents a journal entry he wrote about an encounter with a well-built man in the subway after he had just clicked his picture: “‘Panting heavily, he glared at me, waiting for me to answer his question – “Did you take my picture?” “Yes I did” – thunderous laughter and a clearly amicable pat on the shoulder accompanied his stentorian reaction, as he shouted through the car to the curious crowd of passengers, “Great! With this picture, you’re gonna be rich someday because I’m gonna be famous.”’”

Although he did not personally face any dangerous situations on the subway, Spiller witnessed people being pushed in front of an oncoming train. He recalls a pianist whose hand was chopped off due to this incident. It had to be carried in a plastic bag to the hospital to be sewn back on to her arm, which was unsuccessful. For Spiller, stabbings on the street were far more frequent. “People are so close together that it’s very difficult for a criminal to get away. But still. People were afraid. Because you’re sitting with or standing very close to dangerous-looking people.” This evidently ostracised communities and sections of society who were considered “dangerous” and “unsafe”.

In his experience, New Yorkers liked to present themselves for the picture. One of his photographs features schoolgirls in the subway. He recalled the moment he took the picture: “The door closed. She smiled. One looked around. Two looked at me.” It was a very self-promotional and colourful time, he said.

This image of smiling schoolgirls features on the cover of Spiller’s new book of collected works, Hell on Wheels – New York Subway 1977- 1984. Spiller had generated more than 2,000 images of the subway over eight years in the city. Many of the images became wildly popular, but others have generated controversy, including that image of the schoolgirls, which some considered inappropriate and voyeuristic. Spiller addressed the matter, saying the girls were very aware of being photographed, they were extremely comfortable in the train and seemed to have created their own bubble within the subway. A few years ago, someone approached him, after recognising his mother in the photograph – she was still alive and very happy about the picture.

New York at the time was rebellious, young and daring, and so was the subway. The passengers sitting in front of subway graffiti in Spiller’s new book or the twins in colour-coordinated tube tops show exactly that. Spiller recalled musicians who created music in the subway and of course the graffiti artists – Keith Haring, who was against the gallery model of viewing art, would often be seen covering the walls with his graffiti for people to see just for the price of a ticket.

Spiller claims friendship with many visual artists, such as the graffiti crew Fabulous 5, which included Fab 5 Freddy, who was a popular face in the underground music and art scene, hanging out with artists like Warhol. “I introduced them to a Roman gallery, who was so attracted by these five young guys that [the gallerist] bought canvases for them to spray on and took them back to Rome. This was something contradictory to the idea of street graffiti but great for the Fabulous 5.”

Spiller’s work gives us a glimpse of the late Seventies and Eighties, and their stories and adored and widely recycled aesthetics. It’s a reminder of the creativity that filled that time, where one could interact with artistic work in accessible spaces and share the same crowd as Diana Ross or Warhol for a while. More so, he captures the daily lives of regular people, whose names we may not know, whose family or friends may recognise them in his work one day, like some have. His images draw us towards the person spending a minute buying a hotdog before catching the subway or the drained man on the night train – it’s the magic of the mundane. The last time Spiller was in New York was summer last year, and the change the city has undergone doesn’t sit quite right. “Graffiti does not exist any more, which used to be an inspiring source for others, but annoying for some people,” he reflects. The subway has become clean and the trains run on time, whereas when Spiller was down there photographing the people waiting on the platforms, nobody really knew when a train was coming. He rues this transformation. “When life is so controlled,” he concludes, “there is not much room for wild ideas.”